Art, Indifference, and Ironic Immortality

The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.

—HP Lovecraft, in “The Call of Cthulhu”

“…All my tales are based on the fundamental premise that common human laws and interests and emotions have no validity or significance in the vast cosmos-at-large” (from the letter to the editor accompanying HPL’s submission of “The Call of Cthulhu”)

Lovecraft’s Cosmic Indifference

HP Lovecraft was an amateur philosopher, and through his fiction told the world about his personal philosophy.

Sometimes called “weird realism”, or “cosmicism”, Lovecraft himself called it Cosmic Indifferentism.

Lovecraft was an atheist and a materialist. He was fascinated with the vastness of the universe and the insignificance of human beings in comparison to the incredible expanse of what we are able to perceive.

The insignificance of human beings is the driver behind the creation of the Cthulhu Mythos and HPL’s philosophy of Cosmic Indifference.

Previous philosophies (and even subsequent ones) were theocentric or anthropocentric. Either God sits at the center, or man does. Lovecraft swept those views aside and put the vast universe at the center of his philosophy. Human beings, in Lovecraft’s view, are insignificant in comparison to the cosmos. They don’t matter in the grand scheme of things.

The every day affairs of modern human existence matter to us.

The boss who yelled at us. The kid coming down with a cold. A car hitting the family dog. The wife filing for divorce. Those things matter to us. They are, however, of no consequence in the big picture of things. They simply do not matter at cosmic scale.

This is the horrifying reality that is before us: nothing we care about matters. Nothing in our puny lives is of any significance to the reality of the cosmos.

We are accidental byproducts of the accidental collision of atoms. And that means there’s no ultimate meaning to life.

There is no intelligent design.

Which means there is no God to comfort us in our sorrow, or to share our joy. There is only the material chaos of reality that has no feeling and therefore cannot interact with us. We are alone. Mere flyspecks floating in a vast void.

At first glance, this seems unrelentingly pessimistic. Lovecraft, however, did not see himself as an optimist or a pessimist. Nor a nihilist.

He was a cosmic indifferentist. The vast cosmos has no discernible meaning. It is just atoms. In chaos. And as the cosmos is indifferent to humanity, so it behooves us to view the cosmos with the same indifference. Yet we don’t. We want it to mean something.

The terror of Cosmic Horror is in coming to grips with the fact that there is no essential meaning to anything.

Of course, as the writer of Ecclesiastes notes, There is nothing new under the sun.

HPL’s cosmic indifferentism did not form in a vacuum. It is, in fact, an end product of a line of reasoning that has its roots in ancient Greek philosophical thought.

Let’s take a look at the root that produced Lovecraft’s tree.

Ancient Greek Skepticism

From what we know, the philosophical school of Skepticism was founded by Pyrrho of Elis in the 4th century BC. Little is known about what Pyrrho taught, for he wrote nothing. His teachings were recorded by his student Timon of Philus, whose books have unfortunately not survived, outside of fragments preserved by other authors.

The most well-known form of Skepticism is Pyrrhonism, which was most likely formulated by Aenesidemus in the 1st century BC. It seems Aenesidemus took issue with the Academic Skeptics of his day and formed his own school, claiming it to be a faithful continuation of the teachings of Pyrrho.

Aenesidemus’s Ten Modes are epistemological arguments that effectively demolish any attempt at a claim to “know” anything. In this, we can say that Aenesidemus was the first Proto-Nihilist.

Although the goal of Pyrrhonism was ataraxia (an untroubled and tranquil mind, achieved by the suspension of all judgment), when pushed to their logical conclusion, Aenesidemus’s Ten Modes demonstrate that nothing can be known. And if nothing can be known, then ataraxia is not possible. I cannot be confident that what I’m experiencing is real.

The Pyrrhonists did not go down that rabbit hole. It took the rediscovery of Pyrrhonism in the Renaissance to set Europeans on the road to nihilism.

Existential Nihilism

There are many forms of nihilism. The one we’ll focus on in this little essay is existential nihilism.

Nihilism means the ideology of nothing.

Since the rediscovery of the writings of Sextus Empiricus in the 1500s, philosophers have been utilizing Aenesidemus’s Ten Modes to demolish the Christian worldview established during the late Roman Empire. (Sextus is the Pyrrhonist from whom we know about the school and what they believed. He wrote in the 2nd or 3rd century AD.)

This trend culminated in the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche, who famously declared God is dead.

Although it should be noted that Nietzsche had a very low opinion of Pyrrhonism. I think in part because Nietzsche’s philosophy is a glorification of what man can become when he throws off the restraints of religion and culture and becomes the Übermensch.

Nietzsche’s philosophy is at base optimistic. Doubting everything wasn’t his thing. His philosophy is anthropomorphic. Man is at the center of the universe.

When we stare into the void and realize that all of our beliefs are false, it is then that we are free to become the Übermensch, the Overman, the one who becomes the new god and creates meaning out of a meaningless world for himself.

Nietzsche’s revelation that we had actually ceased to believe what we thought we still believed was too good. Later existentialists latched on to it and formed a nihilistic concept of existence.

Nietzsche would not have approved of the negativism that lies at the root of existentialism. Although he probably would have approved of the ultimate optimism that we find in the systems of Sartre and Camus.

Sartre held the view that people simply create their own values through the choices they make, in spite of the cosmic lack of meaning.

Camus’s leap of faith was a challenge to the meaninglessness of the universe. I will spit in the face of the meaningless void. I will make meaning where there is none.

For Nietzsche, though, the answer to the reality of the Void, was not freewill or the leap of faith, it was the conscious will to power of turning to art, creativity, to impose our order on the chaos of reality.

Is Art the Answer?

In The Birth of Tragedy, Nietzsche posited art as the answer to give meaning to our lives once our previous beliefs had been stripped from us by peering into the void.

Lovecraft took the opposite view, which we see in his short story, “The Music of Erich Zann”. For those unfamiliar with the story, below is a summary.

The mute violinist Erich Zann plays haunting, otherworldly music in a decrepit Parisian garret, observed by the story’s narrator, a student. Zann’s music is unlike anything earthly, described as “weird” and “fantastic,” with a frenzied intensity that seems to channel forces beyond human comprehension.

As the story unfolds, it’s revealed that Zann’s music is a desperate act to ward off or appease a cosmic void—a “blackness” or “infinity” visible through his attic window, which the narrator glimpses as a chaotic, formless abyss.

In the climax, Zann plays with manic intensity as the void seems to invade, only to be consumed by it: the narrator flees, and Zann is presumably lost, his music failing to hold back the cosmic forces. The story ends with the narrator unable to find the street again, emphasizing the unreality and terror of the experience.

For Lovecraft, art is not salvific. Zann attempts to use music to appease the monstrosities of the void, only to have that very music be the drawstring that brings them to his destruction.

There is nothing salvific in HPL’s universe. Art does not tame the Dionysian chaos. It only invites it in for our ultimate destruction.

Nihilism is at the core of both Nietzsche’s and Lovecraft’s philosophies, with two radically different responses.

Nietzsche’s optimism and the Übermensch, along with Camus’s leap of faith, and Sartre’s freewill, provide us with hope in the face of our categorical meaninglessness.

Lovecraft offers no hope other than to turn away from the void before we go mad. In fact, it’s best if we don’t question, don’t explore the unknown. It is in doing so that we get into trouble. That is the horror of Cosmicism and the Cthulhu Mythos.

The Irony of Lovecraft’s Legacy

In line with his belief in Cosmic Indifferentism, Lovecraft expected his memory and his work to pass away unnoticed. If everything has no inherent meaning, then there is no reason to expect anything more. We have no value and our work has no value, because it is meaningless in the face of the great cosmic void.

Nevertheless, HPL wrote stories, carried on a voluminous correspondence with a wide range of people, and even went on trips to visit some of his correspondents. He was not a recluse. He was very active in his particular corner of the writing world.

Upon his death he was mourned by his correspondents and friends, and 2 years after his death his friends August Derleth and Donald Wandrei founded Arkham House to preserve his legacy.

Today, HP Lovecraft is more widely known than ever before. His impact spreads across literature, gaming, the small and big screens, and philosophy. Which is somewhat ironic.

His belief in an uncaring and uninterested universe, where nothing has any inherent meaning, should naturally lead to a position where it would be best if we died as quickly as possible.

Yet Lovecraft, did not passively wait until death took him. He was busy. Busy creating and actively engaged in discussion with his friends and correspondents on a wide range of topics. Which seems to give support to at least Sartre’s position: that we create meaning in the meaningless universe by the choices we make.

Lovecraft made his choices, and in spite of the meaninglessness of it all, he chose to create. And rather than pass away unnoticed, he has achieved a form of immortality.

Living with the Void

Today in the Western world there is an epidemic of ennui and hyper-narcissism. It seems we have looked into the void, are nauseated by what we’ve discovered, and are ignorant of Nietzsche’s salvific art.

Instead, we are living lives which display our inherent meaninglessness and we are grasping at anything to give us the tiniest shred of meaning.

There is the endless scrolling through the social media feed looking for the next dopamine hit.

There is the epidemic of drug use.

Cancel culture was created to wage war on divergent opinions. Only one opinion can survive. The one that validates me. This is hyper-narcissism at play.

There is the self-gratification of influencer culture.

The creation of perfect online personas to cover up who we really are.

The hookup culture’s devaluing of traditional relationships.

We are living out our belief that life has no intrinsic meaning. Everything is hollow. Our lives are unfillable voids. Which is the message of Lovecraft’s Cosmicism.

We’ve seen the void and we’ve become the gods of destruction: self-destruction and cultural destruction.

However, I do not think most of us realize that we’ve looked into the void. The behaviors that we are witnessing are, though, the result of looking into the void. It is chaos in motion. It is the madness Lovecraft prophesied.

Cthulhu Mythos

In Lovecraft’s view it’s a mercy our minds are unable to make sense of all the data we have accumulated and continue to accumulate. We understand in bits and pieces. As HPL noted in the quote opening this little essay.

But should we ever be able to correlate all human knowledge into one understandable whole, then our choices are madness or a retreat into a new dark age. (And we seem to be on the road to the first, even without correlating all human knowledge into one whole.)

At the center of Lovecraft’s fictional universe is Azathoth, the Blind Idiot God. It is asleep at the center of infinity, or ultimate chaos; asleep and dreaming.

The known universe is but a dream Azathoth is dreaming. Should it awaken, everything would vanish. The instantaneous annihilation of existence.

As Lovecraft was an atheist, all of the deities in the Mythos are metaphors and symbols. Azathoth, being blind and an idiot, is a metaphor for the purposeless chaos that dreams the universe into existence.

As a side note, scientists are speculating that our universe is a bubble that arose out of the quantum foam. A limitless sea on which we float. And one day the bubble will burst and we will be no more. Quite interesting that.

But whereas the quantum foam just is, Azathoth is active chaos. Unseeing. Unknowing. Without purpose. A somnolent dreaming an idiot’s dream. A dream of which we are a part.

And the Outer Gods, Azathoth’s children, play their demonic flutes to keep the slumbering chaos asleep and thereby secure their continued existence.

On the other side, Nyarlathotep, the Crawling Chaos, the Messenger of Azathoth, is intelligently evil, in contradistinction to his idiot father, and walks the earth doing the bidding of the Outer Gods and the Great Old Ones to secure their return to earth and the destruction of the human race.

And what of us? How did we arise? We were created by the Elder Things and promptly set aside and forgotten. Unlike the Shoggoth, who were servants to the Elder Things.

So not only are we in a meaningless dream universe, but our own creators don’t care about us.

The cosmos is completely indifferent to us. Just as we are completely indifferent to the existence of ants.

This is the terror behind Cosmic Horror and the Cthulhu Mythos: the horror is not in cosmic malevolence, but in cosmic indifference. This in spite of Nyarlathotep. For he too ultimately doesn’t matter.

Nothing matters.

It’s like finding that special someone, only to discover the person doesn’t even know you exist.

It’s busting your butt at work to do a good job. Every day. Every week. Every month. Every year. Only to discover your boss doesn’t care and you get laid off.

It’s trying to please your parents, to do something to make them proud of you. Only to have them never notice. They never, ever, notice anything you do.

In this day and age when we have more ways than ever before to connect to people, we are experiencing an epidemic of loneliness. And now we who are lonely learn no one cares, no one has ever cared, and no one will ever care. Our fate is to live a long, lonely life and to die alone, with no one caring about our passing.

That is what cosmic horror is all about. Not a single one of us matters in the big picture. There is nothing out there to care about us. Because the only thing that is actually out there is a slumbering idiot who’s blind. And the moment it wakes up, we and everything else vanishes.

So How Do We Live?

In the face of cosmic indifference, how do we live?

In Lovecraft’s fiction, discovery of the truth leads to madness. His fiction is a warning — a warning to not investigate the reality of things. To be content with our little fictions. The fictions that make us think we are important. That we are the center of the world.

Cosmic horror’s value for me is that it makes me think. Makes me think about my life. What meaning do I have if I have no intrinsic meaning or value?

My answer is in the little bit of advice Marcus Aurelius, Roman emperor and Stoic philosopher, gave himself: Life is what you make it.

We are born. We live our lives. And we die. The great question is what do we do with our lives.

The Stoic philosopher Seneca the Younger wrote that life is long enough, if you know how to use it. The problem is most of us don’t know how to use it. We don’t know what to make of our lives. We are in a race with time and we are lost coming out of the gate.

The great challenge for us all lies in learning how to use the time we have today. Seneca said to live our entire lives each day.

In my Pierce Mostyn Paranormal Investigations cosmic horror series, Pierce gradually realizes the monsters never end. We cannot win. We are outnumbered in a cosmos that doesn’t care if we live or die.

His solution is to retire and live a normal life with Dotty Kemper. A house in the suburbs, complete with white picket fence. To be with the person he loves, tinkering on the old cars he enjoys.

But having gazed into the abyss, can Pierce ever be satisfied living what he knows to be a lie? Perhaps. Perhaps not. We might find Pierce’s answer in the forthcoming ninth book in the series.

The question remains, though, can we live a “normal” life if we’ve looked into the void? When we know the true normal? I doubt it. Especially given the current state of western civilization.

We’ve looked into the void and we are self-destructing. We are going mad. Yet, Lovecraft, ironically, found a measure of meaning for himself to fill out the days, instead of taking matters into his own hands to die soon.

Life is what you make it.

Epicurus, believing the universe to be chaos and without meaning, chose to retreat from the world with a group of friends. People who cared about each other. Who took joy in the simple pleasures of life.

I think, if we can, we need to choose to stop and smell the roses and watch the sunset — sharing the experience with a friend.

The cosmos doesn’t care. Friends do. And maybe that’s the antidote to Cosmic Indifferentism. It seemed to work for Lovecraft.

CW

4 responses to “The Nihilistic Void of Lovecraft’s Cosmicism: ”

Dude, when you write an essay, you don’t fool around! But thank you for pulling back the veil on my own outlook. I think I’ve mentioned here before that I came to Lovecraft too early. Responding to a recommendation by a teacher, I arrived at the library in search of hideous, slathering monsters. What I found instead was a rambling gabfest with some sort of nasty creature lurking in the wings but rarely if ever making an appearance. You’d see the ruins of their ancient palaces, and sometimes their minions as in Shadow Over Innsmouth, but he never delivered what I wanted, and I turned away in disappointment. Returning in my 50s, I of course found him fantastic.

And my own veil? Well, I’ve never subscribed to the “Invisible Man in the Sky” religions, as George Carlin called them. Once I encountered Kung Fu, the Carradine series in the early 70s, I tried to pattern myself after his character and identified myself as a Taoist. Rather than bowing to the Invisible Man, what passed for Taoism on the show relied on natural forces to maintain order in the universe. We are, as you say, the random result of those forces in action, and we can thrive by living our lives in harmony with them. I have no idea whether a genuine Taoist would recognize any of this, but I can tell you, it has been a very peaceful, low-stress way to live for the last fifty years. But now I see it articulated in one wonderful sentence:

“Life is what you make it.”

It has been a wonderful ride in my pseudo-Taoist bubble, and the best parts are the ones shared with friends, one of whom is you. So I thank you for this essay, my friend, that strikes maybe deeper than you intended, and for sharing a bit of the road. It continues to be one heck of a ride!

LikeLiked by 2 people

A masterful essay, CW! It helped me better understand Lovecraft’s work, which I appreciate. Unfortunately, it also reinforced what I’ve always felt about my own significance (or lack thereof); but that’s not necessarily a bad thing, as I also believe in being ‘real’. Whether or not anything we do has any cosmic significance whatsoever, we are nonetheless here anyway, like it or not, at least for a little while; so why not make the most of it while we can, instead of just waiting to die? Life is indeed what you make of it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] Threads that Bind on “The Nihilistic Void of Lovecraft’s Cosmicism”, and possible personal […]

LikeLike

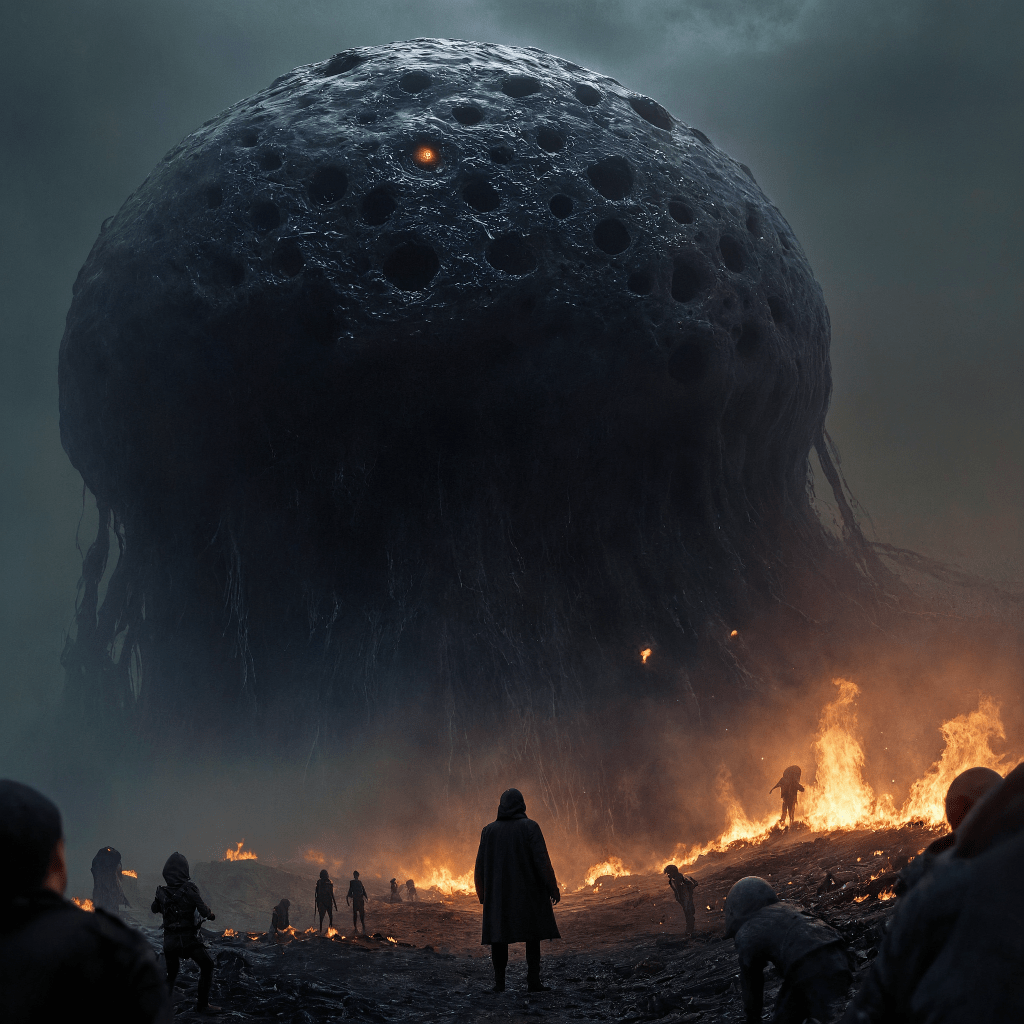

I like those pictures!

LikeLike