Today on Threads that Bind, we delve into another example of the literal and metaphorical ties that connect us—sometimes in the most unsettling ways. Enter anthropodermic bibliopegy: the rare, macabre practice of binding books in human skin.

What part of our psyche would drive us to skin the body of a fellow human being, tan his or her skin, and then use it for bookbinding? Kind of gives a twist to the old saying, I’m going to tan your hide.

Peaking in the 19th century, these volumes blur the line between artifact and atrocity, raising questions about ethics, medicine, and mortality. What drove people to encase knowledge in the very flesh it described? Let’s uncover this dark chapter.

The practice, though rumored in ancient times, gained traction in the 19th century amid medical advancements and access to cadavers. Doctors, with bodies from executions or unclaimed patients, tanned skin like animal leather—often from criminals as a form of posthumous punishment. The term “anthropodermic bibliopegy” emerged in the 1940s, but examples date to the French Revolution, including a 1793 Constitution volume allegedly in human skin. By 2022, the Anthropodermic Book Project confirmed 18 genuine cases out of 50 tested, mostly 19th-century medical texts. Interesting that the majority of books bound in human skin were medical texts. What does that say about the doctors who did the binding?

Methods mirrored traditional bookbinding: skin was removed, tanned, and stretched, indistinguishable from calf or pig without testing. Peptide mass fingerprinting (PMF), developed by the project, analyzes collagen to confirm human origin—inexpensive and reliable. Ethical lapses abound; skins often came from executed criminals or poor patients without consent.

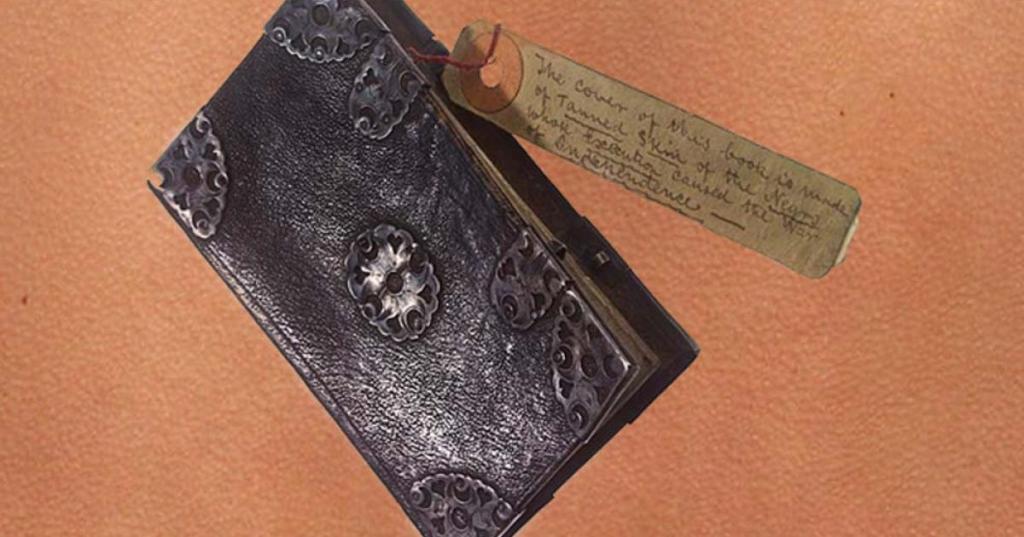

Notable 19th-century examples include Narrative of the Life of James Allen (1837), bound in the highwayman’s own skin at his request, now at Boston Athenaeum. John Horwood’s 1821 execution papers, bound in his skin by surgeon Richard Smith, feature a skull embossing and reside in Bristol’s M Shed. William Burke’s skin (1829) formed a pocketbook after his dissection for body-snatching murders. Dr. John Stockton Hough bound several texts in Mary Lynch’s skin (died 1869 of trichinosis), including Recueil des secrets (1635) and anatomy works, now at Philadelphia’s College of Physicians. Harvard’s Des destinées de l’âme (1880s) used an unclaimed mental patient’s skin; in 2024, the binding was removed for ethical reasons. Brown University’s John Hay Library holds four: Vesalius’s De Humani Corporis Fabrica (1579), two Dance of Death editions, and Mademoiselle Giraud, My Wife (1891). Other confirmed: Joseph Leidy’s An Elementary Treatise on Human Anatomy (1861) from a Civil War soldier’s skin.

These bindings often matched content—anatomy texts in skin as a “fitting gesture.” Motivations ranged from punishment (criminals) to curiosity (doctors), with rare erotica like an anonymous BDSM poem. Ethical debates intensify; institutions like Harvard grapple with repatriation, influenced by laws like the UK’s Human Tissue Act.

The practice waned as ethics evolved, but surviving volumes challenge us: are they historical curios or desecrated remains? Are these volumes a testament to the Dr. Frankenstein residing in us all? Or are they simply a testimony to our brutal insensitivity to our fellows.

In binding knowledge with flesh, they eternally thread human curiosity to horror.

2 responses to “Human Skin Books: The Grim Bindings of the 19th Century”

Brings a new twist to the term “horror book” as well. Hell of a study, as always. You always give us something to ponder.

LikeLike

Very interesting! I wonder if they ever did this in Nazi Germany; or were they more focused on burning books than binding them? I remember hearing they did some other things with the skin of deceased concentration camp prisoners. Guess I’ll have to look that up sometime (when I decide I need another dose of human depravity).

LikeLike